Understanding the realities of palliative care in acute hospitals: Insights from multidisciplinary clinicians

An article written by Dr Claudia Virdun, Senior Lecturer - Palliative & End of Life Care, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Flinders University

As the number of people living with and dying from advanced serious illness continues to rise, hospitals remain a central setting for care in the final stages of life. Yet, despite strong evidence about what patients and families value in high-quality palliative care, delivering this care within acute hospital environments remains a persistent challenge.

In our recent qualitative study, we spoke with 88 clinicians—nurses, doctors, and allied health professionals—across three acute hospital wards. Our aim was to understand the barriers and enablers to integrating palliative care into everyday hospital practice. Our study uncovered critical challenges that have persisted for decades and clear opportunities for improvement. [1]

Defining palliative care: A persistent misunderstanding

One of the most striking insights was the ongoing confusion surrounding what palliative care actually entails. While many clinicians could articulate a definition aligned with the World Health Organization’s definition, their day-to-day practice often reflected a narrower view—one that equated palliative care with terminal care or specialist referral.

It’s good to link them in early but most of the time I feel like our practice has been to refer when someone is dying imminently as opposed to planning in advance if that makes sense. (Ward 3, Medical 3, with 1 year experience)

This misunderstanding was not limited to clinicians. Patients and families frequently associated palliative care with imminent death, which in turn influenced when and how care was initiated. Clinicians described a “grey zone” where patients were seriously ill but still receiving active treatment, and uncertainty about when to engage palliative care often led to delayed or missed opportunities for holistic support.

… it’s distressing to both me and my residents [medical team members] when we see patients are suffering and we feel powerless to get the palliative care team involved or we are stuck in the grey zone... it’s when they’re stable but they’re badly stable where we know we feel this is not going in the right direction but we feel a bit powerless and we don’t know whether to just keep treating them actively or get palliative care involved earlier. (Ward 1, Medical 7, with 4 years’ experience)

Shared care models: Navigating complexity

The study highlighted the complexities of shared medical governance in palliative care. While specialist palliative care teams were valued for their responsiveness and emotional support, the boundaries between teams were often unclear. This led to tensions around roles and responsibilities, particularly in the absence of designated inpatient palliative care beds.

Clinicians proposed innovative models to address these challenges, including co-located beds, joint ward rounds, and embedded palliative care physicians within specialty teams. These suggestions reflect a desire for more integrated, collaborative approaches that prioritise continuity and person-centred care.

I actually think we should have a palliative care person that works for us… I feel like if we employed a palliative care person, I’m not sure how that would work with them and the palliative care team, but I think if we felt like they were part of our team and they had some understanding of where we were coming from more… It would mean also that we would be more likely to reach out for advice and those sorts of things. (Ward 1, Medical 4, with 26 years’ experience)

Building capability and confidence

Clinicians across disciplines expressed a strong desire for education and mentorship to enhance their confidence in providing palliative care. Junior staff, in particular, felt underprepared for complex conversations and decision-making. Allied health professionals sought greater clarity on their role within multidisciplinary teams.

Grads it’s something that scares them and they still are scared because they know that its coming… and when we run our transition programs it is something that they consistently bring up as something that does worry them. About what am I going to do? How am I going to make that person feel safe? And how do I deal with conversations of palliative care with my patients when they’re asking me things that maybe I don’t feel confident about? But also how do we advocate for our patients? How do we explain palliative care to them? Like how do they get educated on palliative care when we don’t know palliative care? (Ward 1, Nursing 8, with 9 years’ experience)

Importantly, participants also emphasised the emotional demands of palliative care and the need for staff support. Providing compassionate care in the face of suffering requires not only clinical skill but also emotional resilience—something that must be nurtured through thoughtful organisational support.

Competing priorities in acute care

The acute hospital environment presents inherent challenges to prioritising palliative care. Clinicians described the difficulty of balancing the needs of patients requiring curative interventions with those needing comfort-focused care. Time pressures, staffing constraints, and organisational priorities often meant that palliative care was deprioritised, particularly when patients appeared stable.

This tension was compounded by the cognitive shift required to move between acute, life-saving interventions and end-of-life care. Clinicians spoke candidly about the mental and emotional toll of this dual responsibility.

Like your brain needs to switch between the very acute setting you know doing everything you could to save to someone’s life and then straight change to someone that we are withdrawing from treatment and just making them comfortable. So that’s two completely different brain sets sometimes it’s just difficult. (Ward 2, Nursing 3, with 12 years’ experience)

The role of environment in quality care

Physical space matters. Participants described how the design of hospital wards—limited private rooms, constant noise, and lack of family-friendly areas—impacted their ability to provide dignified, restful care. Some clinicians envisioned simple yet meaningful changes, such as family rooms, double beds, and permission for families to personalise the space with comforting items.

Those wards are gross, you know you’re in a four-bed bay, they’re mixed genders, they’re dirty, there’s a really high sort of movement across the ward in terms of patients but then also the number of staff up there is extreme. It’s not a place that constitutes rest for anyone. (Ward 1, Allied health 3, with 5 years’ experience)

These environmental factors are not peripheral; they are central to the experience of care for patients and families.

Moving forward: A call for system-level change

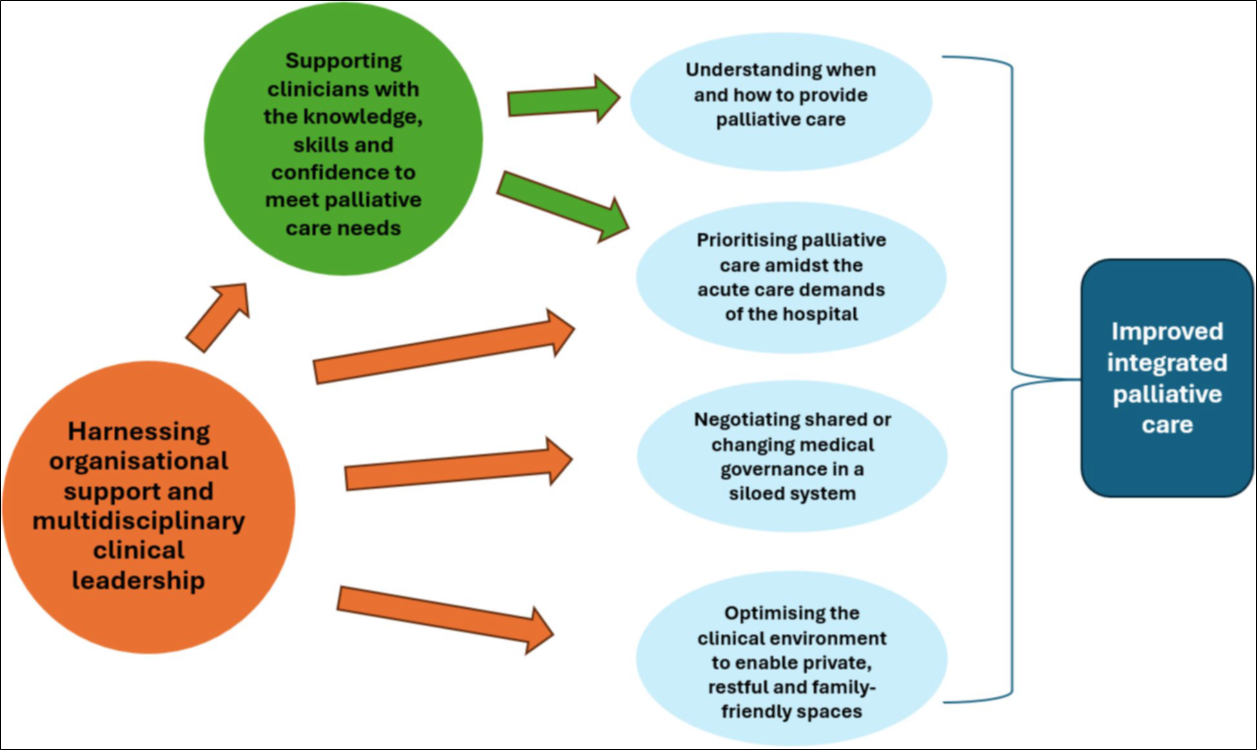

Our findings underscore that improving palliative care in hospitals requires more than individual skill development. It demands system-level change—organisational support, leadership across disciplines, and environments that enable privacy, rest, and family inclusion. We have shown this within Figure 1 below:

Fig. 1 Key challenges and opportunities impacting inpatient integrated palliative care

Clinicians are ready to lead this change. What they need is the time, space, and support to do so. If we are to meet the needs of people living with advanced serious illness, we must listen to those providing the care. Their insights offer a roadmap for meaningful, sustainable improvement.

References

- Virdun C, Singh GK, Yates P, Phillips JL, Mudge A. Understanding the acute care context to inform palliative care improvements: A qualitative study of hospital-based multidisciplinary clinicians. BMC Palliative Care. 2025;24:185.

Author

Dr Claudia Virdun

Senior Lecturer - Palliative & End of Life Care, College of Nursing and Health Sciences

Flinders University