Understanding public health palliative care

An article written by Associate Professor Jason Mills

With death and dying increasingly recognised as a public health concern, public health approaches to palliative care have been adopted in a global effort to promote healthy dying and, in the process, reframe the experience of death, dying, loss and caregiving. [1] These approaches include the active engagement and participation of everyday people, and the (social ecology) world around them. That is, not only patients and their families living with diagnoses of serious illness or life-limiting conditions—but also the people throughout their social networks, local communities and broader society. However, these approaches are intended to complement, not supplant, professional service provision; and community activity is not the sole focus of public health palliative care.

While the term ‘public health palliative care’ may seem self-explanatory, some confusion appears to exist with conflation apparent between discrete public health approaches – such as the ‘compassionate communities’ model, [2] and the much broader remit pertaining to the field of public health palliative care itself. [1] The purpose of this introductory piece, as part of the following Palliative Perspectives series, is to briefly introduce each component of public health palliative care while clarifying and situating their place within the field.

Palliative care is widely recognised as a public health concern, with both structural and social determinants of health affecting health outcomes and access to palliative care, generally; and health inequities for disadvantaged populations, more specifically. The field of public health spans a broad range of approaches, from the traditional foci of surveillance, epidemiology and disease control/prevention, to a more contemporary focus on health promotion through education, empowerment and participation. It should therefore be noted that public health palliative care incorporates ‘new public health’ practice methods. These new public health approaches place the public—everyday people and communities—as active participants in their own health and wellbeing, and recognise the centrality of settings and social determinants of health in promoting health-related quality of life. [3]

Given that quality of life is a key focus for palliative care, health promotion for healthy dying is not an oxymoron. It is the social context of death and dying that provides the basis for public health palliative care. The theory and practice of public health palliative care recognises that death, dying, loss and caregiving is context-bound, as a social experience that affects everyone without exception. [1] And this has significant implications for the organisation and delivery of care for those living with dying across the lifespan, particularly in relation to the re-orientation of health services for health promotion.

Looking ‘upstream’, one key emphasis of public health approaches to palliative and end-of-life care is the empowerment and ‘citizen activation’ of social capital and collective compassion within groups; a social model of care commonly referred to as compassionate communities, or in a broader context, compassionate cities. Together, they draw from the World Health Organization's Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, in strengthening community action and creating supportive environments to improve individual capabilities and enhance community capacity for end-of-life care – with prevention and community development as a key enablers. [1,3]

At the same time, ‘downstream’ activities led by clinical/health service providers—both generalist and specialist—focus on promoting health and quality of life to the extent possible within those settings. Downstream and upstream strategies can work in tandem, supporting each other in the process. [3]

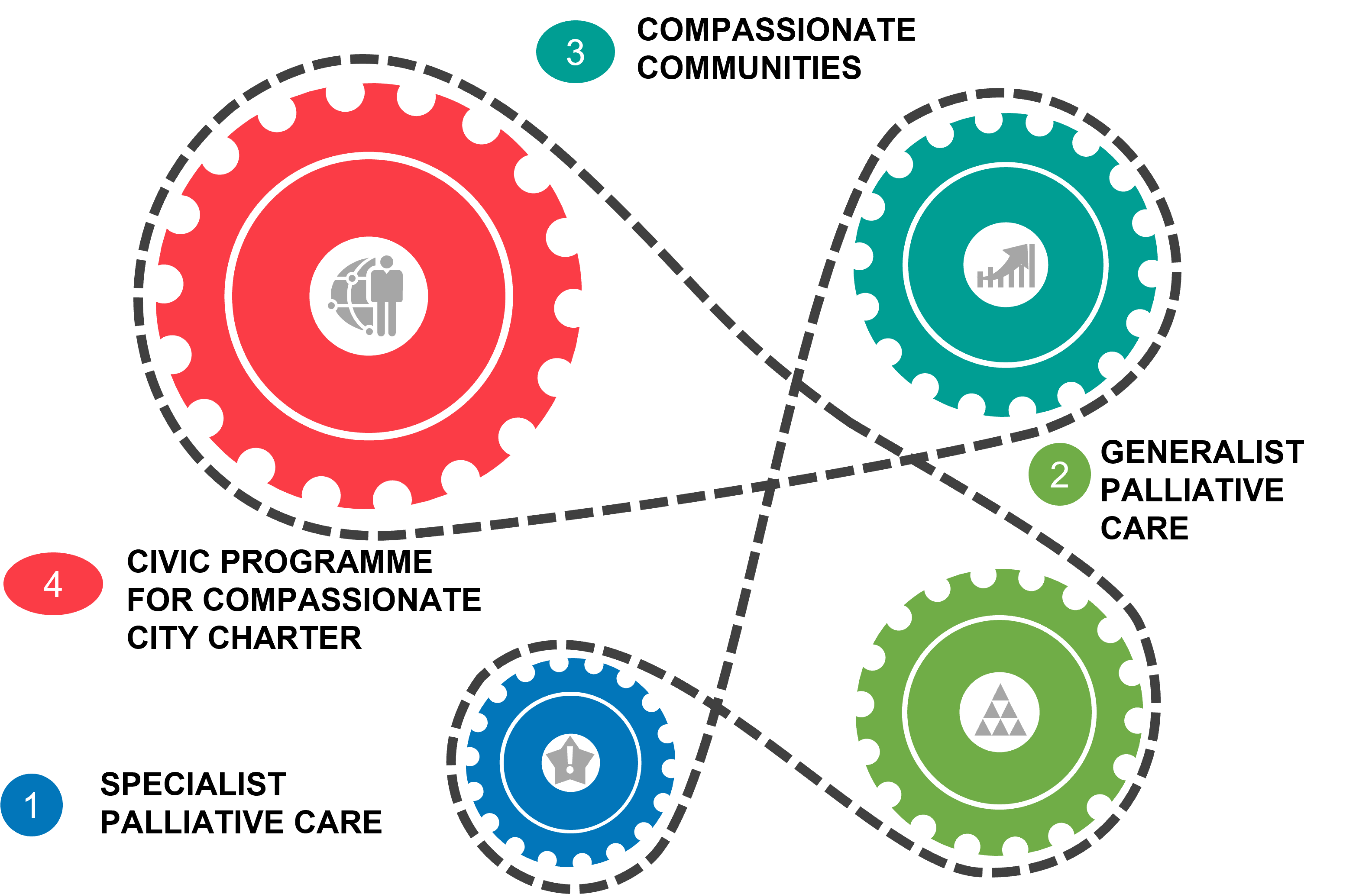

In the New Essentials model of palliative care, [4] we find the key components of public health palliative care: (1) Specialist palliative care; (2) Generalist palliative care; (3) Compassionate communities; and (4) Civic programme for Compassionate City Charter. These components are illustrated below, which each cog playing a vital, interrelated role, in promoting healthy dying—through upstream and downstream activities—in collaborative partnerships engaging in palliative and end-of-life care. Viewed in its entirety, public health palliative care is not confined to just one component of the model.

This model, and the broader field, is examined in great detail within the Oxford Textbook of Public Health Palliative Care. [5] In this Palliative Perspectives series, expert chapter authors from this text will share their expertise and examples in alignment with each relevant component of public health palliative care.

Authors

Associate Professor Jason Mills

Senior Nurse Academic and Researcher

Flinders University, Research Centre for Palliative Care, Death and Dying

References

- Abel J, Kellehear A. 2022. Public health palliative care: Reframing death, dying, loss and caregiving. Palliative Medicine, 36(5), 768-769.

- Mills J, Abel J, Kellehear A, Noonan K, Bollig G, Grindod A, Hamzah E, Haberecht J. 2024.

The role and contribution of compassionate communities. The Lancet, 404(10448), 104-106.

- Rosenberg JP, Mills J, Rumbold B. 2016. Putting the ‘public’ into public health: Community engagement in palliative and end of life care. Progress in Palliative Care, 24(1), 1–3.

- Abel J, Kellehear A, Karapliagou A. 2018. Palliative care—the new essentials. Annals of Palliative Medicine, S3-S14.

- Abel J, Kellehear A. 2022. Oxford Textbook of Public Health Palliative Care. Oxford University Press.