Technology keeping palliative care patients at home – the CASA aspiration

An article written by Dr. Thilo Schuler

We recently published the CASA (Continuous Assessment and Support Alerts) feasibility study exploring the use of wearable sensors and targeted short smartphone surveys (ecological momentary assessments (EMAs)) in palliative care patients and their caregivers. [1, 2] Most of this blog will focus on our motivation for this work and the long-term aspiration to which we are working.

Problem and aspiration

People with life-limiting cancer wish to spend precious time with loved ones in a familiar environment. Consequently, home-based palliative care - as opposed to an inpatient setting - is preferred by most patients but often not achieved, particularly in the final weeks. One reason is that people may have symptoms that are difficult to control at home. Another reason is that a great deal is asked of non-professional caregivers (friends and family) in order to maintain the intense level of care required.

Family and friends play a pivotal role in providing home-based palliative care along with professional caregivers. UK data demonstrated that most family caregivers spend up to 19 hours per week caring for the patient and in the last days of a patient’s life, this number escalates to a median of 70 hours. [3] The physical and emotional toll of providing such challenging care can lead to distress and burnout of caregivers. Starr et al captured the effects on caregivers’ sleep in their qualitative study entitled ‘It was terrible, I didn’t sleep for two years’. [4] This under-appreciated and under-managed problem can also affect the patient’s situation including the need for short- or long-term inpatient care.

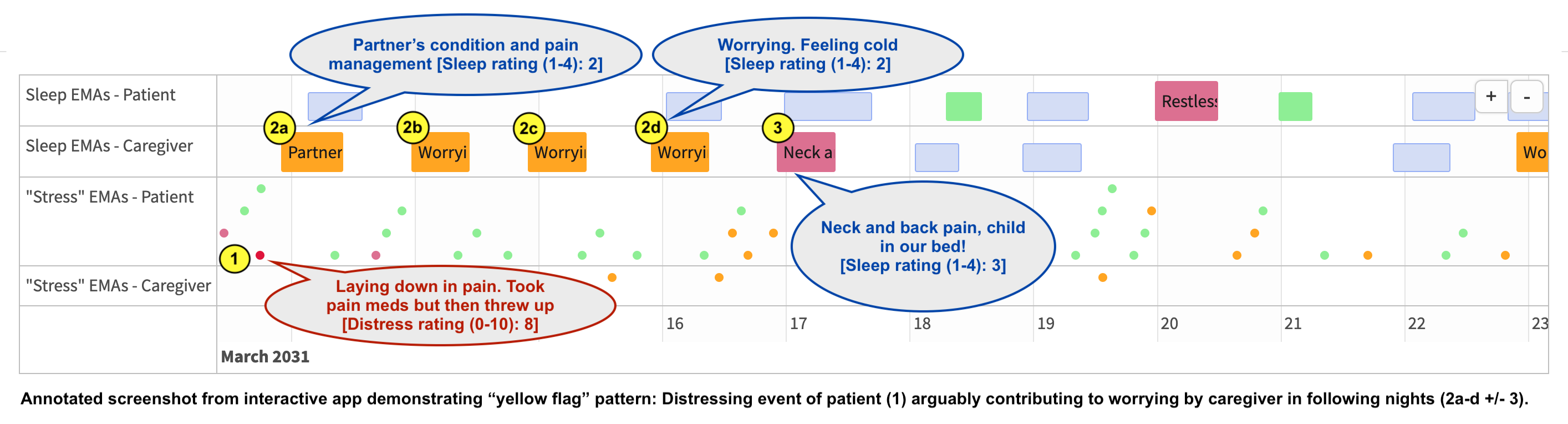

The CASA feasibility study was our initial step towards a vision of smart integration of technology into home-based palliative care. The aspiration is to provide proactive, personalised support that maximises patients’ time at home without compromising on symptom control. Recognising the key role of caregivers, we hypothesise that technology can monitor both the patient and the caregiver in an unobtrusive and resource-efficient manner. The goal is to detect “yellow flag” patterns that can trigger targeted professional assessment and proactive support to reduce avoidable crises.

CASA feasibility study

Patients and caregivers wore consumer-grade wearable sensors for 5 weeks. Sensor-detected “stress” (using a heart rate variability algorithm) where breaching an individualised threshold triggered an EMA survey on their smartphone. All participants received a daily sleep EMA survey, a weekly symptom survey (Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS)), and a post-study experience survey.

We recruited 15 patients and their caregivers (n=30) at an outpatient palliative care clinic. Daytime sensor wear-time and weekly symptom survey completion were 73% and 78% respectively. These adherence results, the granular data collected (sensor data stream and 1395 surveys), the fast recruitment, and participants’ perceived value of this approach support its feasibility. Sleep disturbance was equally prevalent in patients and caregivers, but the predominant causes differed (physical causes dominated among patients but for carers it was mental causes such as worrying). [2] The quantity and severity of “stress” events were higher in patients than in caregivers. Experience survey responses were overall very positive.

Next steps

Building on the CASA feasibility study we are in the process of setting up a study to collect wearable data from patients and caregivers at a much larger scale. We plan to use artificial intelligence (AI) methods to identify “yellow flag” patterns. If successful, we would then test a proactive support intervention triggered by “yellow flags” in a multi-site, randomised trial.

The following figure demonstrates an example “yellow flag” pattern captured from dyad 10. This and all other collected EMA responses can be viewed in an interactive app (access via https://thiloschuler.me/project/casa/; for data privacy reasons a dynamic random time shift is applied).

References

- Schuler T, King C, Matsveru T, Back M, Clark K, Chin Det al. Wearable-Triggered Ecological Momentary Assessments Are Feasible in People With Advanced Cancer and Their Family Caregivers: Feasibility Study from an Outpatient Palliative Care Clinic at a Cancer Center. J Palliat Med. 2023 May 3. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0535. Epub ahead of print.

- Schuler T, Currow D, Clark K, Back M. Letter to the Editor: Sleep Disturbances in People with Advanced Cancer and Their Informal Caregivers: A Digital Health Exploration. J Palliat Med. 2022 Jun;25(6):850-851. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0125.

- Grande G, Rowland C, van den Berg B, Hanratty B. Psychological morbidity and general health among family caregivers during end-of-life cancer care: A retrospective census survey. Palliat Med. 2018 Dec;32(10):1605-1614. doi: 10.1177/0269216318793286. Epub 2018 Aug 21.

- Starr LT, Washington KT, McPhillips MV, Pitzer K, Demiris G, Oliver DP. "It was terrible, I didn't sleep for two years": A mixed methods exploration of sleep and its effects among family caregivers of in-home hospice patients at end-of-life. Palliat Med. 2022 Dec;36(10):1504-1521. doi: 10.1177/02692163221122956. Epub 2022 Sep 23.

Dr. Thilo Schuler

Radiation Oncology Advanced Trainee at Royal North Shore Hospital

PhD candidate in Clinical Informatics at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University